NATIVE AMERICAN WARRIOR ART AND ARTIFACTS

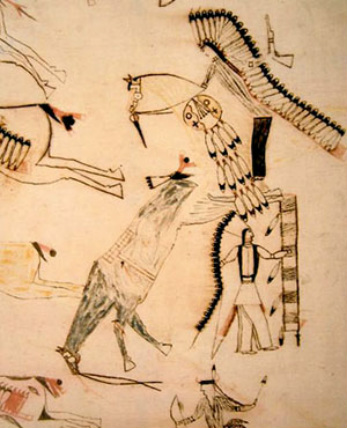

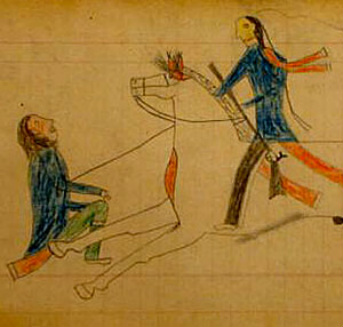

Native American warriors decorated their garments, shelters and their weapons with imagery and devices recording their war exploits before they had contact with Europeans. With the introduction of new materials and technology, not only was the experience of war transformed but also the recording of those experiences. Pencils, pens, paints, paper – the new tools allowed for more detail in their pictorial records, resulting in important art objects of the Indian Wars.

This show features the art documents known as ledger drawings as well as a painted muslin, recently discovered with provenance to the American soldier who collected it. This muslin, which measures eight feet long and nearly three feet wide, allowed the artist a freedom to compose his battle scenes on a field many times larger than the confines of a ledger page. The result is a sweeping panorama that tells a much larger story than a ledger page would permit. One enters the scene from the right, as the scene unfolds to the left, the opposite of how Western culture generally view things. This unfolding of the story from the peacefulness of home life to the fury of battle has a filmic quality, a narrative that Mike Cowdrey illuminates in his attached essay. The show also features a representative group of Indian-used weapons from this era. These weapons are, for the most part, decorated with brass tacks that also record exploits (Cheyenne mirror club) or imbue the weapon with symbolic power (White Dog’s club). Of course, not only the tacks but the weapons themselves are products of the displacing culture with whom the Natives were at war. We also see the continuation of forms that pre-date contact, such as the sculptural bird forms that terminate the Akicita gunstock club and the three-blade club. While the bird is naturalistically depicted on the three-blade club, with tacks used to represent the eyes, on the gunstock, the form is comparatively abstract. Carving the form on the club surely imbued it with the animistic power of a bird of prey, able to see its victim from a distance and to swoop in by surprise as well as to quickly escape, if not disappear. Two of the clubs terminate in disc forms (White Dog’s club and the mirror club). Does this reflect the sun, the circle of power or is it merely a device to help one hold the club? Or is it both? Two of the objects in the show contain mirrors: the Cheyenne club that has parallel rows of tacks on one side and X-crossed tacks on the other, recording coups and kills respectively, is covered on both sides with mirrors. The Ute beaded bag was made to hold a mirror. Of course, the primary use of a mirror is for grooming purposes but this magical device has gripped the imagination of all cultures – even our own where it is hardly the novelty that it was on the Plains in the 19th century. My grade-school children know that it is seven years bad luck to break a mirror – how more mythic could it be when we use the biblical number to connote the severity of the bad luck? We can only conjecture how important these devices were to those warriors – grooming for battle, reflecting the sun to signal one’s allies and undoubtedly adding good luck to the occasion. One tomahawk in the show is decorated with square shank brass tacks; another one has pewter inlay around the mouthpiece and where the head meets the haft. The process of applying metal inlay to wooden hafts and stone pipes was done by native blacksmiths beginning in the eighteenth century. The tacks on the other tomahawk do not appear to be in a pattern that is anything other than decorative. Perhaps it was enough to personalize an object with tacked adornment. Whatever the intention, we now view it as a personal artifact of a warrior fighting to preserve a way of life that would soon disappear. Holding this in one’s hands provides a direct link to that world, an immediate experience that is not duplicated by books or film. There is something about handling the object itself that gives us a different way of knowing, a more direct experience, than being told about it. Hold it where it was held in its active life and feel the weight, the balance, the energy – past, present and potential. We are far removed from those times that have passed, of course, but we are linked by the physical reality of the object. I believe that this sensual joy (because this way of knowing is a joy) is a central reason why we collect. John Molloy |