TOY CRADLES FROM THE PLAINS & PLATEAU

Essay by Katharine Vann

view the show, NATIVE AMERICAN ANTIQUE TOY CRADLES ->

|

On view at John Molloy Gallery, April 15 - May 14, 2018, is a series of toy Native American cradleboards from the Plains and the Plateau. The traditional baby-carriers of many indigenous peoples across North America on display demonstrate that young girls played with emblems of motherhood from an early age. On view is an early pony bead example from the Warm Springs people, as well as an array of examples from the Ute, the Apache, the Nez Perce, the Lakota, the Kiowa-Comanche, among others.

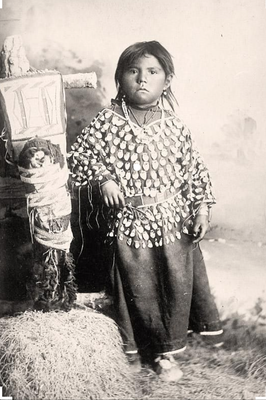

Used widely across North America, the majority of cradleboards were made of hide, cloth, or woven basketry. Miniature cradleboards are the most represented toy in historical Native American photographs. Illustration 1 shows an example of a young Crow child, posed for a photograph next to a doll strapped into a miniature cradleboard. The ubiquity of photographs such as that shown in illustration 1 suggests that toy cradleboards were widely played with by Indian youth throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. |

|

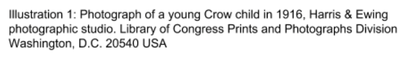

Illustration 2 depicts an image of a young Southern Cheyenne Girl dated to 1895, resting a toy cradleboard on her knees that contains a porcelain doll. What is curious about this picture is that the porcelain figure in the cradleboard is a mass-produced Frozen Charlotte doll, popular among young white girls during this period. This image raises a number of questions, including how these dolls were acquired by young Indian girls, as well as the implications that the whiteness of the doll had upon the young Indian girl playing with it.

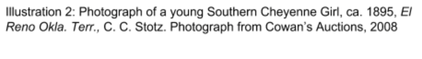

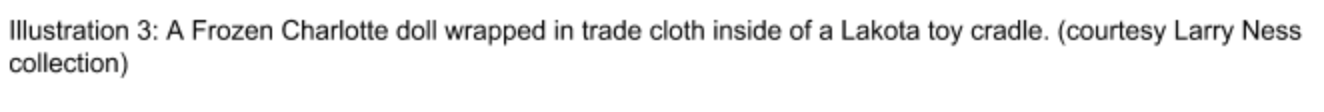

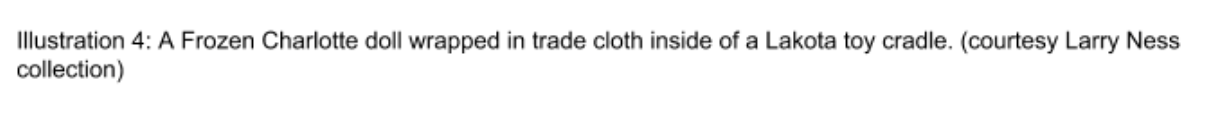

Scholars of Native American art have written extensively about cross-cultural trade and the flow of mass-produced materials at trading outposts, where Frozen Charlotte dolls were likely acquired. Illustrations 3 and 4 show images of two of these dolls wrapped in trade cloth inside of Lakota toy cradles. Both exhibit colorful beadwork that incorporate traditional designs, made using glass beads and red stroud trade cloth. Glass beads came into use in decoration among Native artists of the Great Lakes in 1675 as a result of their exchange in the fur trade (Adrosko 1990.) Swaddled in Lakota designs, these Frozen Charlotte dolls showcase a blending in cross-cultural traditions and evidence the longstanding incorporation of European materials into indigenous material culture. The dolls also hint at different kinds of cross-cultural histories that involved not only the transfer of materials from the West but also the transfer of Western values. |

|

The dolls shown in illustrations 3 and 4 are not the only documented examples of Frozen Charlotte dolls used within Native American toy cradleboards. Historian Mary Jane Lenz noted in her book, Small Spirits, that throughout the nineteenth century Plains dolls “sometimes incorporated bisque or china heads of European manufacture,” and by the end of the century, such dolls became particularly popular among the southern Plains (Lenz, 2004: 63.) The question, however, remains as to why Frozen Charlotte dolls became so popular among the people of the Plains, as well as whether they had the same cultural significance for indigenous communities as they did for white children during this period. |

|

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FROZEN CHARLOTTE DOLLS

Frozen Charlotte dolls were miniature ceramic figures sold throughout the nineteenth century across Europe and America (Engmann, 2007.) Originally designed in Germany in the 1840s and 1850s, they became so popular in the 1870s in United States that local companies began producing them onsite. Often referred to as “ten-cent,” or “one-penny” dolls, Frozen Charlottes were the cheapest and most widely sold figures in the United States during the late nineteenth century (Engmann, 2007:16.) Frozen Charlotte dolls would have been easily affordable for many Indians living on reservations towards the end of the nineteenth century, and examples in archaeological sites have been found from across the North American Continent, in the homes of white settlers, Native Americans, and Chinese immigrants. |

|

Frozen Charlotte dolls from this period were purchased for For Euro-American children, even the name “Frozen Charlotte” evoked the cultivation of Victorian values. The phrase “Frozen Charlotte” is derived from an American folk song called “Young Charlotte” based on a 19th-century ballad about a vain girl who refused to cover up her party dress while riding to a ball on a frigid winter's night. The girl in the story dies from the cold: "Fair Charlotte was a stiffened corpse/ And her lips spake no more"; and her demise reminds us to forsake vanity in favor of basic common sense (Walsh, 2003). In Cooley’s (2013) creative work, it is suggested that the story was meant “to teach girls to avoid their vainness, to cover up on sleigh rides at night.” The unclothed Frozen Charlotte dolls enabled young women to learn about the virtues of modesty by learning to sew and produce garments for their dolls. In purchasing Frozen Charlotte dolls, Victorian mothers encouraged their children to learn propriety and subservience. It is possible that Native American parents gave their children Frozen Charlotte dolls because of their perceived moralizing potential. However, it seems more likely that the dolls were included in cradleboard toys as they provided blank figurines for their children to mold and incorporate into pre-existing Native traditions. |

FROZEN CHARLOTTE DOLLS AND INDIAN SCHOOLS

Fragments of Frozen Charlottes from the late nineteenth century uncovered at an Indian school in Arizona suggest that dolls may have been used as educational tools to help convert Indians to Euro-American lifestyles. The Phoenix Indian School formed a component of the Federal Government’s Policy to assimilate Indian children into American Society following the confinement of Native people to reservations in the 1880s (Lindauer, 1998). Following its eventual closure in 1988, the Phoenix Indian School Archaeological Project was initiated to assess the school’s turn of the century trash dump, 230 by 165 feet in size. 160,000 artifacts were recovered from the dig containing refuse dating from 1891 to 1926. This refuse included 136 fragments from 108 porcelain dolls.

The education program at the Phoenix Indian School was originally developed at Carlisle Indian School, with a particular focus on educating young women in domestic work. In the 1870s, Congress authorized army officer Richard H. Pratt to convert military barracks at Carlisle, Pennsylvania into the Carlisle Indian School, the first federal off-reservation boarding school for Indian youth (Lomowaima, 1993:299.) Captain Richard Henry Pratt, famed founder of the Carlisle Indian School, wrote (1987), "I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked." At school, young men learned blacksmithing and carpentry while young women focused on household training, including sewing and cooking. As Owen Lindauer suggested, “For girls, caring for one's doll (baby) was a way of introducing socialization skills and gender-role identification at an early age” (Lindauer, 1998.) It is possible then, that the dolls found at the Phoenix Indian School, were used as teaching tools to help convert Indian women to “virtuous” feminine trades.

Fragments of Frozen Charlottes from the late nineteenth century uncovered at an Indian school in Arizona suggest that dolls may have been used as educational tools to help convert Indians to Euro-American lifestyles. The Phoenix Indian School formed a component of the Federal Government’s Policy to assimilate Indian children into American Society following the confinement of Native people to reservations in the 1880s (Lindauer, 1998). Following its eventual closure in 1988, the Phoenix Indian School Archaeological Project was initiated to assess the school’s turn of the century trash dump, 230 by 165 feet in size. 160,000 artifacts were recovered from the dig containing refuse dating from 1891 to 1926. This refuse included 136 fragments from 108 porcelain dolls.

The education program at the Phoenix Indian School was originally developed at Carlisle Indian School, with a particular focus on educating young women in domestic work. In the 1870s, Congress authorized army officer Richard H. Pratt to convert military barracks at Carlisle, Pennsylvania into the Carlisle Indian School, the first federal off-reservation boarding school for Indian youth (Lomowaima, 1993:299.) Captain Richard Henry Pratt, famed founder of the Carlisle Indian School, wrote (1987), "I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked." At school, young men learned blacksmithing and carpentry while young women focused on household training, including sewing and cooking. As Owen Lindauer suggested, “For girls, caring for one's doll (baby) was a way of introducing socialization skills and gender-role identification at an early age” (Lindauer, 1998.) It is possible then, that the dolls found at the Phoenix Indian School, were used as teaching tools to help convert Indian women to “virtuous” feminine trades.

|

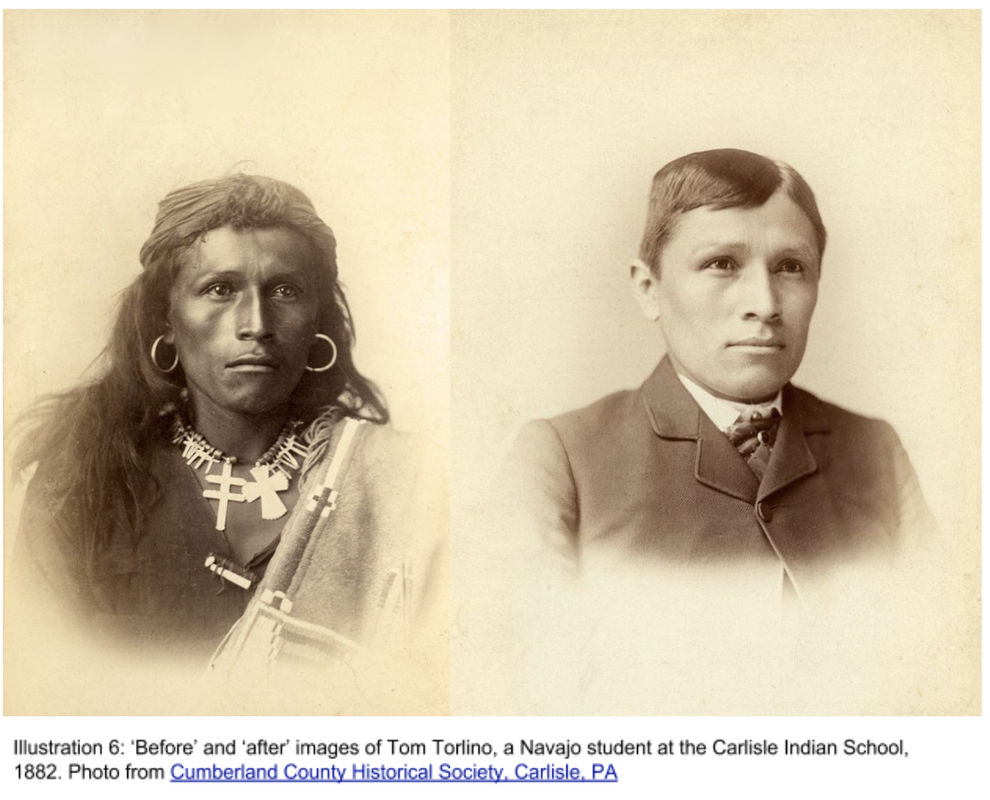

At boarding schools, the new image of the female Indian body was created according to the dictates of Victorian decency and domesticity. This study of the ways the "body itself is invested by power relations" (Foucault 1979:24) depends upon a critical analysis of the boarding school as an institutional training ground where the colonized were meant to learn subservience. As anthropologist Tsianina Lomawaima has suggested, “the regimentation of the external body was the essential sign of a new life, of a successful transformation.” Before and after photos were part of this culture of imperialism. At Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania in the 1880s, for example, orphaned Indian children were made to cut their hair, remove any hints of tribal affiliation and were dressed to look Western. Before and after images such as those featured in illustration 6 hint at the popularity of such transformations that show Native peoples’ journeys from ‘savage’ to ‘civilized’.

|

As simulacra of ourselves, parallels can be drawn between young Victorian girls’ dressing of dolls’ bodies and Indian Schools dressing of Native peoples bodies. Anthropologist Lomawaima suggested that Indian Schools acutely focused on westernizing Indian girls’ attire, hairstyle, and posture as part of their cultural assimilation efforts (Lomawaima, 1993.) Similarly, perhaps the dolls found at the Phoenix Indian School (such as the doll shown in illustration 5), were given to Indian boarding school children to teach them not only the practical and ‘feminine’ trade of sewing, but also to educate them in the perceived moralizing potential of looking European.

One of the Frozen Charlotte cradle dolls on view at the John Molloy Gallery features a rosy pink complexion, raising the question of whether the skin color of these dolls impacted Indian girls’ self-perception (illustration 3.) Although most of the dolls were white, it was not uncommon for Frozen Charlottes from this period to feature painted faces, with light pink shades considered the “freshest colors of youth” (Coleman et al. 1986.) In the 1930s and 1940s, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark sought to uncover whether playing with dolls of another ethnic background impacted a child’s psychiatry (Chin, 1999: 256.) Their findings suggested that playing with white dolls negatively impacted black girls’ self-perception. Similarly, it could be argued that playing with white porcelain Frozen Charlotte dolls increased feelings of difference for the young Indian girls who played with them.

In the 1990s, anthropologist Elizabeth Chin conducted a case study in New Haven to more deeply explore how children perceived playing with ethnically diverse dolls (Chin, 1999.) What her findings suggested was that for many young American black girls, the colour of a doll’s skin did not determine how they perceived the doll’s ethnicity. Rather, she suggested that children readily incorporate dolls of other ethnicities into their worlds through a process called “racial imagining” (Chin, 1999: 263.) In essence, Chin argued that children materially and symbolically work on dolls to incorporate them in their culture. Racial identity thus becomes complex and multifaceted rather than fixed and rigid. As such, the idea that playing with white dolls negatively impacted young Indian girls’ perception of themselves, does not necessarily hold weight. In keeping with Chin’s argument that dolls are always reimagined by children and incorporated into their cultural worlds, the cradle toys in illustrations 3 and 4 similarly exhibit instances of European dolls that have been wrapped in indigenous beadwork to incorporate them into Lakota culture. Therefore instead of viewing the use of Frozen Charlottes by Native audiences through a decidedly Euro-American lens, it is important to focus on how Native American peoples incorporated dolls and ceramics into their various local traditions.

Further, historical evidence suggests that Native Americans had been using ceramic decorations on their cradleboards long before the spread of Frozen Charlotte dolls. This may suggest that Frozen Charlottes may have been valued by some Native American communities for their materiality rather than for their use as dolls. In the late seventeenth century, French fur trader Nicholas Perrot observed that the Iroquois used glass and porcelain ornaments on their cradleboards (Ellick, 2002: 14.) Porcelain began being exported into the North American continent from Canton through the Northwest Coast during the late nineteenth century, traded across the continent in exchange for fur pellets. However, porcelain was most commonly encountered by Native American peoples during the late seventeenth century not in the form of dolls, but as beads (Ellick, 2002). It is therefore disputable whether porcelain as a material held standalone value for the indigenous communities across North America.

In the 1990s, anthropologist Elizabeth Chin conducted a case study in New Haven to more deeply explore how children perceived playing with ethnically diverse dolls (Chin, 1999.) What her findings suggested was that for many young American black girls, the colour of a doll’s skin did not determine how they perceived the doll’s ethnicity. Rather, she suggested that children readily incorporate dolls of other ethnicities into their worlds through a process called “racial imagining” (Chin, 1999: 263.) In essence, Chin argued that children materially and symbolically work on dolls to incorporate them in their culture. Racial identity thus becomes complex and multifaceted rather than fixed and rigid. As such, the idea that playing with white dolls negatively impacted young Indian girls’ perception of themselves, does not necessarily hold weight. In keeping with Chin’s argument that dolls are always reimagined by children and incorporated into their cultural worlds, the cradle toys in illustrations 3 and 4 similarly exhibit instances of European dolls that have been wrapped in indigenous beadwork to incorporate them into Lakota culture. Therefore instead of viewing the use of Frozen Charlottes by Native audiences through a decidedly Euro-American lens, it is important to focus on how Native American peoples incorporated dolls and ceramics into their various local traditions.

Further, historical evidence suggests that Native Americans had been using ceramic decorations on their cradleboards long before the spread of Frozen Charlotte dolls. This may suggest that Frozen Charlottes may have been valued by some Native American communities for their materiality rather than for their use as dolls. In the late seventeenth century, French fur trader Nicholas Perrot observed that the Iroquois used glass and porcelain ornaments on their cradleboards (Ellick, 2002: 14.) Porcelain began being exported into the North American continent from Canton through the Northwest Coast during the late nineteenth century, traded across the continent in exchange for fur pellets. However, porcelain was most commonly encountered by Native American peoples during the late seventeenth century not in the form of dolls, but as beads (Ellick, 2002). It is therefore disputable whether porcelain as a material held standalone value for the indigenous communities across North America.

CONCLUSIONS

Numerous factors come into play when evaluating why Native American Plains communities chose to incorporate Frozen Charlottes and porcelain dolls into cradleboard toys used by their children. Firstly, we must consider the materiality of bisque and porcelain. Before European contact, accounts from across North America indicate that dolls were made from materials sourced from surrounding environments. Among the Plains Indians, oral testimonies indicate that dolls were often made from locally available materials, such as wood, cloth, and hide (Lenz, 2004.) Although we assume that ceramic toys are too fragile for real play, Frozen Charlottes were perhaps more durable than the fabric rag dolls often seen in cradleboards during the late nineteenth century. Wrapped in fabric, cradleboard Frozen Charlotte dolls are protected from fractures and are padded from potential damage.

Further, as noted above, Frozen Charlotte dolls were incredibly cheap to purchase as they were mass produced in the United States from the late 1870s onwards. Frozen Charlottes were thus readily available for trade and purchase at affordable prices. Rather than focusing on a unidirectional flow of Euro-American values to Native peoples, we therefore need to look at how and why Native people adapted and incorporated new objects into their material cultures.

It is therefore imperative to open up a dialog for Native understandings of Frozen Charlotte dolls rather than to assume that they were incorporated into indigenous cultures as part of a civilizing mission. We cannot rule out that purchased as blank canvases, Frozen Charlotte dolls supplied the ideal mannequins for manufacturing clothing for, providing opportunities for young women to continue beadwork traditions laid out for centuries for their communities.

Numerous factors come into play when evaluating why Native American Plains communities chose to incorporate Frozen Charlottes and porcelain dolls into cradleboard toys used by their children. Firstly, we must consider the materiality of bisque and porcelain. Before European contact, accounts from across North America indicate that dolls were made from materials sourced from surrounding environments. Among the Plains Indians, oral testimonies indicate that dolls were often made from locally available materials, such as wood, cloth, and hide (Lenz, 2004.) Although we assume that ceramic toys are too fragile for real play, Frozen Charlottes were perhaps more durable than the fabric rag dolls often seen in cradleboards during the late nineteenth century. Wrapped in fabric, cradleboard Frozen Charlotte dolls are protected from fractures and are padded from potential damage.

Further, as noted above, Frozen Charlotte dolls were incredibly cheap to purchase as they were mass produced in the United States from the late 1870s onwards. Frozen Charlottes were thus readily available for trade and purchase at affordable prices. Rather than focusing on a unidirectional flow of Euro-American values to Native peoples, we therefore need to look at how and why Native people adapted and incorporated new objects into their material cultures.

It is therefore imperative to open up a dialog for Native understandings of Frozen Charlotte dolls rather than to assume that they were incorporated into indigenous cultures as part of a civilizing mission. We cannot rule out that purchased as blank canvases, Frozen Charlotte dolls supplied the ideal mannequins for manufacturing clothing for, providing opportunities for young women to continue beadwork traditions laid out for centuries for their communities.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adrosko, Rita J., ‘A “Little Book of Samples”: Evidence of Textiles Traded to the American Indians’, in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, (1990), pp. 65-75

Chin, E, Ethnically correct dolls: toying with the race industry, in American Anthropologist, 1999

Engmann, Rachel, “Ceramic Dolls and Figurines, Citizenship and Consumer Culture in Market Street

Chinatown, San Jose”., Lab Methods. Professor Voss, 3.21.2007

Fernandez, Elizabeth, “Still She Never Stirred”: Frozen Charlotte Dolls of the Victorian Era”, 2015 [accessed 04/01/2018] (https://www.academia.edu/12251298/_Still_She_Never_Stirred_Frozen_Charlotte_Dolls_of_the_Victorian_Era?auto=download)

Illick, Joseph E., American Childhoods, 1st edn (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002)

Lenz, Mary Jane, Small Spirits: Native American Dolls from the National Museum of the American Indian, 1st end (Washington: University of Washington Press, 2004)

Lindauer, Own, “Archaeology of the Phoenix Indian School”, Archaeology, May 27, 1998 [accessed 04/02/2018] (https://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/phoenix/)

Lomawaima, Tsianina, “Domesticity in the Federal Indian Schools: The Power of Authority over Mind and Body”, in American Ethnologist, Vol. 20, No. 2 (May, 1993), pp. 227-240

Sanchez, John and Stuckey, Mary E., “From Boarding Schools to the Multicultural Classroom: The Intercultural Politics of Education, Assimilation, and American Indians”, in Teacher Education Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 3, Advancing Educational Opportunities in a Multicultural Society (Summer 1999), pp. 83-96

“The Fur Trade Era: 1650s to 1850s: A Shot History of Wisconsin”, Wisconsin Historical Society [accessed 04/01/2018] (https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3585)

Walsh, Linda, “Frozen Charlotte Dolls - How Adorable But Tragic”, Victorian Traditions [accessed 04/02/2018] (https://victoriantraditions.blogspot.com/2016/04/frozen-charlotte-dolls-how-adorable-but.html)

Adrosko, Rita J., ‘A “Little Book of Samples”: Evidence of Textiles Traded to the American Indians’, in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, (1990), pp. 65-75

Chin, E, Ethnically correct dolls: toying with the race industry, in American Anthropologist, 1999

Engmann, Rachel, “Ceramic Dolls and Figurines, Citizenship and Consumer Culture in Market Street

Chinatown, San Jose”., Lab Methods. Professor Voss, 3.21.2007

Fernandez, Elizabeth, “Still She Never Stirred”: Frozen Charlotte Dolls of the Victorian Era”, 2015 [accessed 04/01/2018] (https://www.academia.edu/12251298/_Still_She_Never_Stirred_Frozen_Charlotte_Dolls_of_the_Victorian_Era?auto=download)

Illick, Joseph E., American Childhoods, 1st edn (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002)

Lenz, Mary Jane, Small Spirits: Native American Dolls from the National Museum of the American Indian, 1st end (Washington: University of Washington Press, 2004)

Lindauer, Own, “Archaeology of the Phoenix Indian School”, Archaeology, May 27, 1998 [accessed 04/02/2018] (https://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/phoenix/)

Lomawaima, Tsianina, “Domesticity in the Federal Indian Schools: The Power of Authority over Mind and Body”, in American Ethnologist, Vol. 20, No. 2 (May, 1993), pp. 227-240

Sanchez, John and Stuckey, Mary E., “From Boarding Schools to the Multicultural Classroom: The Intercultural Politics of Education, Assimilation, and American Indians”, in Teacher Education Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 3, Advancing Educational Opportunities in a Multicultural Society (Summer 1999), pp. 83-96

“The Fur Trade Era: 1650s to 1850s: A Shot History of Wisconsin”, Wisconsin Historical Society [accessed 04/01/2018] (https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3585)

Walsh, Linda, “Frozen Charlotte Dolls - How Adorable But Tragic”, Victorian Traditions [accessed 04/02/2018] (https://victoriantraditions.blogspot.com/2016/04/frozen-charlotte-dolls-how-adorable-but.html)