JAMES HAVARD

|

Unquenchable Fire: James Havard’s Recent Paintings

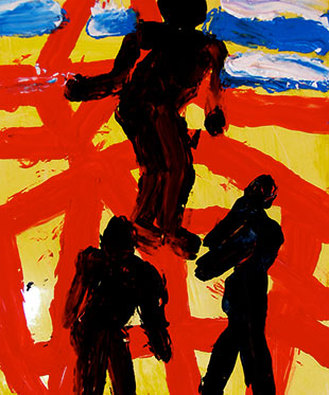

(more Havard images) James Havard’ current exhibition at John Molloy Gallery features fourteen of the feisty artist’s most recent canvases, all painted within the last six months. It has been too long since New Yorkers were treated to the works of this New Mexico-based artist, who right now is painting up a storm as if he were four decades younger than his 77 years. Hands down, his new paintings are some of the boldest, most passionate work he has ever made in this six-decade career. Though these recent abstractions are notably small in scale they explode with vibrant, texture loaded, impastoed color and ricocheting shapes. Their impact is immediate and visceral. Forty years ago, the Galveston, Texas-born Havard was critically hailed as a pioneering, if somewhat eccentric, “abstract illusionist” during the era when macho minimalists dominated American contemporary art even as Photo-Realism and the stealthy reintroduction of content challenged that minimalist hegemony. During the 1980s Havard’s paintings began to include thickening layers of paint, more collaged elements, and fewer squiggles of paint and optical illusions. He had already fallen under the spell of Santa Fe and was leaving New York in the rear view mirror. Actually, Havard’s artistic trajectory has been one only marginally involved with shifting art world trends and fashions. He has seemed to regard the art scene with a kind of stubborn independence about going his own way. His life story is an essential American success story. He was raised on a farm, and an agricultural scholarship got him to Houston State College. Subsequently he made his way to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he evolved from painting delicately traditional still-lifes to embracing expanded techniques and developing a creative reach that turned him to abstraction. His career can in fact be divided into three broad periods: realism (1960s), abstract illusionism (1970s), and abstract expressionism with tribal and outsider influences (1980s and beyond). In 1992 I wrote about James Havard’s work, after he had moved to Santa Fe in 1989, (an environment seeming to suit him so perfectly that it’s where he remains today, having now set up his studio in a garage attached to the facility where he currently lives after a stroke in 2006 made it difficult to walk but did not diminish his painting). His fascination with Native American culture was evidenced by his highly informed personal collection of artifacts. And his artistic direction had shifted to incorporating the influence of tribal cultures into his paintings. Inspiration came from Zuni pots, Navaho and Hopi masks, and the vivid quillwork of the Sioux. The paintings were becoming eloquent homages not only to the New Mexico landscape but also to the native expressions of Hopi, Sioux, Navaho, Cheyenne and Zuni embodied in their beadwork, pottery, ceremonial clothing, and masks. Drawing with color, Havard’s layered images wove together implicit and explicit iconographic and cultural references, incorporating into abstractions symbols he adopted from Native American tribal art and culture. The red heart line of animals still appears in abbreviated form his latest work. The new small paintings are pure color explosions; two of them are dominated by a large red, many fingered glove shape, like a monster hand troweled in with a palette knife, against acid yellow and spring green backgrounds. One of these paintings includes the outline of tiny human figure scratched into a corner of the picture. “The Conversation” becomes a kind of primitive Adam and Eve depiction, the woman scratched together in blue, the man a fully blackened figure, dominating the couple, as they emerge from a vivid yellow ground animated by red, black and white scribbled lines, perhaps symbolic of snakes. The figures of black men reappear in several other paintings such as “Roughnecks.” Could this make figure perhaps be the artist’s roughneck father? These works are the productions of a poet totally involved with what the spontaneities of paint can do, the offerings of a humanist, an anthropologist who refuses to repeat himself. His fierce new paintings distil the experience gained throughout his lengthy career to address what matters to him most; using what he needs most and disregarding trends and styles. Now in his sixth decade of making art, James Havard has distilled his vision to its essences. Alexandra C. Anderson is an art critic and the former editor in chief of Art & Antiques Magazine. … . indeed. - Alexandra C. Anderson |